I have never elsewhere had such an opportunity to observe how much more beautiful reflection is than what we call reality. The sky, and the clustering foliage on either hand, and the effect of sunlight as it found its way through the shade, giving lightsome hues in contrast with the quiet depth of the prevailing tints, — all these seemed unsurpassably beautiful when beheld in upper air. But on gazing downward, there they were, the same even to the minutest particular, yet arrayed in ideal beauty, which satisfied the spirit incomparably more than the actual scene. I am half convinced that the reflection is indeed the reality, the real thing which Nature imperfectly images to our grosser sense. At any rate, the disembodied shadow is nearest to the soul.

Nathaniel Hawthorne: Entry September 18, 1841 from

Passages from the American Note-Books – Vol. II

The parallels between Bert Haanstra’s film Mirror of Holland, for which he won a Golden Palm at the 1951 Cannes film festival, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s reflections (pun intended) are remarkable but certainly coincidental. Haanstra was during his lifetime one of the Netherlands most popular filmmakers. More information on him can be found at BERT HAANSTRA.NL.

Ado Kyrou wrote about Mirror of Holland in his article A Dutch Avant-Garde Filmmaker – Bert Haanstra, which appeared in l’âge du cinéma Nº 6.

Many people still believe that the world is unchangeable, that we perceive and only should perceive its bark, commonly detailed by newspapers and so-called realistic cinema.

Bert Haanstra knows that the “real life”, that was so dear to Rimbaud, is made of sensitive mirrors behind the intrusions, where the encounter of unknown sights will make us delve deeper into the knowledge of ourselves.

Considering this, it’s easier to understand why Kyrou praised Haanstra for making “a ‘realistic’ film without special effects and superimpositions” while at the same time designating him as an Avant-Garde filmmaker.

Kyrou also welcomed Haanstra’s next short film Panta Rhei. For one thing, because of the Heraclitean implications of its title, but also for being to his knowledge the first poetic illustration of dialectics.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

A Forest: Afterimage

I never began by consulting the amusement pages to find out what film might chance to be the best, nor did I find out the time the film was to begin. I agreed wholeheartedly with Jacques Vaché in appreciating nothing so much as dropping into the cinema when whatever was playing was playing, at any point in the show, and leaving at the first hint of boredom – of surfeit – to rush off to another cinema where we behaved in the same way, and so on.

André Breton: As In A Wood (transl. Paul Hammond) from: The Shadow and Its Shadow

Nevertheless certain movie theaters in the tenth arrondissement seem to me to be places particularly intended for me, as during the period when, with Jacques Vaché we would settle down to dinner in the orchestra of the former Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques, opening cans, slicing bread, uncorking bottles, and talking in ordinary tones, as if around a table, to the great amazement of the spectators, who dared not say a word.

André Breton: Nadja, 1928

Night fell, and trying to reach the others, we got lost in a maze of sunken paths. After calling in vain, Breton, evoking one of his familiar fantasies, that of a naked woman suddenly emerging from nothing, started getting anxious. A blinding flash strikes and illuminates in front of us a fantastic landscape, followed immediately by a thunderclap that petrifies us. Breton, in panic, grabbed my hand — She’s there he tells me when another flash exposes the dark turn of the sunken path. I feel it …

Marcel Duhamel: Raconte pas ta vie

At the end of one afternoon, last year, in the side aisles of the “Electric Palace”, a naked woman, who must have come in wearing only her coat, strolled, dead white, from one row to the next.

André Breton: Nadja, 1928

Surreality will depend on our will toward complete disorientation from everything (and it goes without saying that you can disorient a hand by isolating it from its arm, that this hand takes on more value as a hand, and also that when speaking of disorientation, we are not thinking only about its spatial possibilities). (…) Things are called upon to do something other than what’s usually expected.

André Breton: Notice to The Hundred Headless Woman

Surrealist criticism, extremely influential in France especially in film criticism, is virtually absent in England, where the ‘poetry of pulp fiction’ is correspondingly infra dig. The nearest equivalent to this interest is ‘camp’ but this, being essentially satirical, is its diametrical opposite. (…) For reasons of puritanism and class snobbery alike, English criticism in the ‘good taste’ tradition has no terms , still less antennae, with which to discriminate between the sensitive and the insensitive use of pulp imagery (…).

Raymond Durgnat: Franju

But one of the maladies of culture is the effort to smooth away the contradictions in it. It’s caught up in what Marcuse criticises, a kind of colonisation of the imagination. A standardisation of it. Standardisation by good taste, impoverishment by good taste. Freud, Breton, Marxism all help demystify that. Or should. For obvious reasons I’m interested in the plurality of moralities in our culture. Black ‘bad’ meaning ‘good’; artists who force you out of yourself.

Raymond Durgnat: ‘Culture Always is a Fog’

… largely neglected by the film-criticism establishment… Most of the films discussed test the limits of contemporary (middle-class) cultural acceptability, mainly because in varying ways they don’t meet certain “standards” utilized in evaluating direction, acting dialogue, sets continuity, technical cinematography, etc. Many of the films are overtly “lower-class” or “low-brow” in content and art direction. However, a high percentage of these works disdained by the would-be dictators of public opinion are sources of pure enjoyment and delight, despite improbable plots, “bad” acting, or ragged film technique. At issue is the notion of “good taste”, which functions as a filter to block entire ares of experience judged – and damned – as unworthy of investigations.

Andrea Juno / Victor Vale: Incredibly Strange Films

Give me black and white, subtitles and a tiny budget, and I’m impressed. I really like snotty, elitist theaters in New York like Cinema III (my favorite because it’s so comfortable and the ticket price is always expensive), or the Paris where if you ask for popcorn they look at you as if you’re a leper asking for heroin and sneer, “Really! We don’t have refreshments.” I’m so used to audiences yelling back to the screen in grind houses that it’s a real break to sit with a well-behaved audience. I never eavesdrop in these theaters because the conversations are generally maddeningly pretentious. It’s also a problem to laugh out loud at something only you may find funny (especially if it’s a German film – Germany is not ever funny to these audiences). These cinema buffs are very touchy about humor and will turn around and scowl right in your face if they think you laugh is inappropriate.

Guilty Pleasures in: Crackpot – The Obsessions of John Waters

As a result of saying it can show anything, cinema has abandoned its power over the imagination. And, like cinema, this century is perhaps starting to pay a high price for this betrayal of the imagination – or, more precisely, those who still have an imagination, albeit a poor one, are being made to pay that price.*

Chris Marker: A Free Replay – Notes on Hitchcock’s Vertigo

Photo by Weegee

* Too bad I don’t have the text available in its original French version. If one consults the German translation (in Kämper / Tode: Chris Marker Filmessayist) of the text, one sees that one sentence is completely omitted from the English translation. This and another divergence give a quite different edge to the quote. Here my slightly altered translation which corresponds to the German version:

As a result of saying it can show anything, cinema has abandoned its power over the imagination. See the two versions of CAT PEOPLE. And, like cinema, this century is perhaps starting to pay a high price for this betrayal of the imagination – or, more precisely, those who still have an imagination, albeit a poor one, are being paid very well.

Addendum, July 8, 2014:

A force de se raconter qu’il peut tout montrer, le cinéma a abdiqué ses pouvoirs dans l’imaginaire. Voir les deux versions de Cat People. Et tout comme le cinéma, ce siècle est peut-être en train de payer très cher cet abandon de l’imaginaire -ou plus précisément il est en train de le payer chèrement à ceux qui en ont encore un, de très bas étage, mais encore vivant.

The full article in French can be found at LIMINAIRE.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

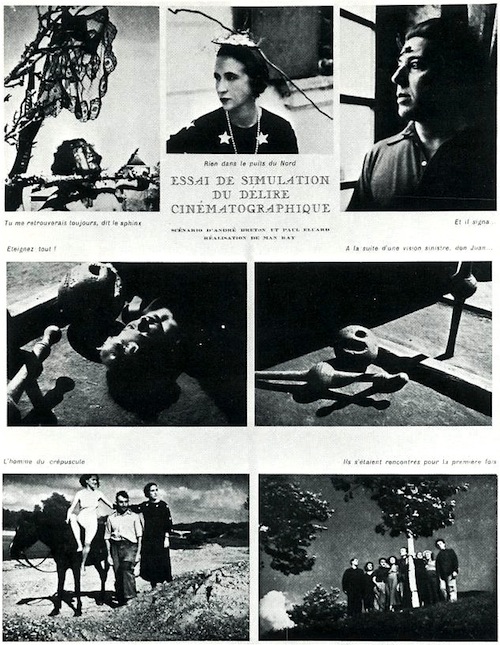

You would always find me again, says the sphinx – Nothing in the north well – And he signed … – Extinguish everything! – Following a sinister vision, Don Juan … – The twilight men – They were meeting each other for the first time

In the summer of 1935 Man Ray began the shooting of a film at Lise Deharme’s country house in southern France. The other participants were Paul and Nusch Eluard, Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton. Nothing remained from this attempt at simulating cinematographic delirium but the stills and captions above, which appeared in the Cahiers d’art (N° 5-6, 1935). In his autobiography Man Ray relates the course of events.

Breton and Eluard spent a day mapping out a scenario in which all were to take part. There were sequences of the women, strangely attired, wandering through the house and in the garden. A farmer’s daughter nearby, whom we’d seen galloping across the country on a white horse without a saddle, was persuaded to repeat the ride before my camera, I would have liked to have her nude for the act, but that was out of the question. She was given a one piece white bathing suit, which at a distance, and in movement, might produce the desired effect. In one scene, Breton sits at a window reading, a large dragonfly poised on his forehead. But André was a very bad actor, he lost patience, abandoned the role. I don’t blame him, secretly I have always detested acting, making believe. The best part of the shot was the end, where he got into a temper. This was not acting. After a few more sessions, during which I was having trouble with my instrument — for it jammed often, losing half the takes, I abandoned the operation, to everyone’s regret. On our return to Paris I salvaged what I could — it looked promising but there was not enough fo a short.

Man Ray: Self Portrait

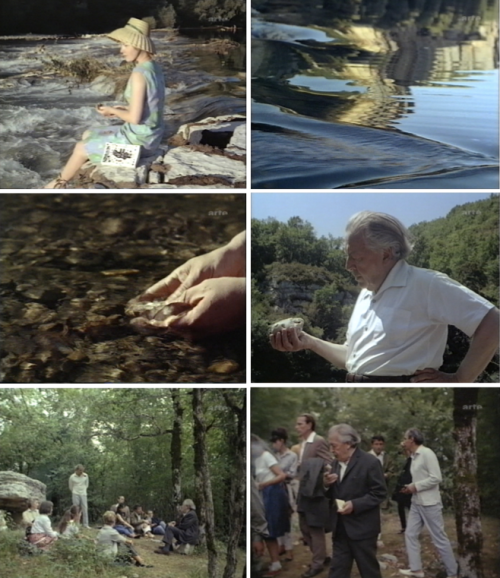

In 1964 Jacques Brunius, director and highly gifted jack-of-all-trades, convinced producer Pierre Braunberger[1] to finance a documentary which would present the surrealist group from within. Robert Benayoun joined in as screenwriter of Le Surréalisme, as the project was entitled by now[2]. Edmond Richard was hired as cinematographer and principal photography began in and around Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, where Breton had a summer house. Several sequences were shot which evolved around group activities like the chase for agates[3] at the shores of the river Lot, a crayfish meal which included a happening of Jean Benoît and a game of L’un dans l’autre[4] in the woods.

But the shooting was strained. Robert Benayoun had aspirations to co-direct the film. Matters were further complicated by the fact that Brunius, an experienced director, was used to carefully plan his shots and to film on schedule whereas newcomer Benayoun had an improvisational approach. There were also tensions among other participants. Mainly about everyone getting their share of screentime. The resulting rushes seemed to please no one. Once again filming made Breton lose his temper and nobody was willing to finish the film. Nevertheless the unedited footage still exists. Film archivist Raymond Borde managed to save it and put it into storage in the Cinémathèque de Toulouse[5].

References: Raymond Borde: Un film interrompu: Le Surréalisme – Archives N° 54, June 1993

Paul Hammond: The Shadow and its Shadow, 2000

Jean-Pierre Pagliano: Brunius, 1987

Screencaps from André Breton par André Breton by Dominique Rabourdin

1 One of the most important producers of the nouvelle vague, Pierre Braunberger was on very good terms with Breton. Interestingly, for a short time he was co-proprietor of the Éditions du Sagittaire. In the publication Cinemamemoire he claims to be responsible for the reedition of The anthology of black humor in 1950.

2 Brunius pursued this project since he was approached by the Cinématheque Française to make a film on surrealism for the Mémoires du monde series. An earlier title was Le hasard objectif.

3 When in 2003 Breton’s collection was sold at auctions in the Hôtel Drouot some commentators were surprised that besides his collection of art worth a several million Euros, he also held many objects in his possession which were hard to estimate. to say the least, like his collection of waffle irons, holy water fonts and … stones.

Last year when we approached, under a light rain, a bed of stones that we had not yet explored along the Lot, the suddenness with which several agates, which had an unusual beauty for the region “caught our eyes”, convinced me that every further step would offer more beautiful ones and over a minute I had the perfect illusion to set foot in earthly paradise.

André Breton: Language of Stones

4 It should be well known that the Surrealists took playing very seriously. The most famous Surrealist game is certainly the exquisite corpse. Here a description of one into another:

One player withdraws from the room, and chooses for himself an object (or a person, an idea, etc). While he is absent the rest of the players also choose an object. When the first player returns he is told what object they have chosen. He must now describe his own object in terms of the properties of the object chosen by the others, making the comparison more and more obvious as he proceeds.

Alaistair Brotchie, Mel Gooding: A Book of Surrealist Games

In short, inventing metaphors on the spot. You could for example describe a lion’s mane by means of a match flame. See for a contemporary use of this principle the sweded films in Michel Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind.

5 Benayoun would later use some of the footage as well as ideas from his screenplay in the TV-documentary Passage Breton.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 3 Comments

Tags: André Breton, Cinema, Edmond Richard, Essai de simulation du délire cinématographique, Film, Jacques Brunius, l'un à l'autre, Le Surréalisme, Lise Deharme, Man Ray, Paul Eluard, Pierre Braunberger, Raymond Borde, Robert Benayoun, surrealism

…I prepared a film screening in the Palais de Chaillot dedicated to the cinéma insolite*. André Breton would have acted as host for the event. The special about this screening would have been to show that in failed or mediocre films there are scenes or shots of unexpected beauty which amount to surrealist exaltation.

But when it came to putting up the posters, I suddenly felt Breton’s anguish to appear in public. He told me that he feared repressions from Tzara against whom he had intervened recently at the Sorbonne. Therefore I suggested to get security guards to protect him and eventually, fearing that he would cancel his appearance at the last moment, I called off the screening to his profound relief.

Georges Franju in M. – M. Brumagne: Franju – Impressions et aveux

* Insolite means literally, unusual. According to Kate Ince, who wrote a monography on Franju, it is “an eruption of the discontinuous in familiar continuity”.

Franju planned to include L’hôtel du libre échange in the program.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

Only a few months ago I was able to satisfy myself, while pondering the single theme of a remarkable film entitled Berkeley Square – the new occupant of an old castle manages, by bringing back to life in his hallucinations those who occupied it in former times, not only to mingle with them but also, as he takes part in their activities, to solve the problem of his present behaviour, a most difficult sentimental problem – that the myth of spirits and of their possible intercessions is still very much alive.

André Breton: Nonnational Boundaries of Surrealism (1937) in Free Rein

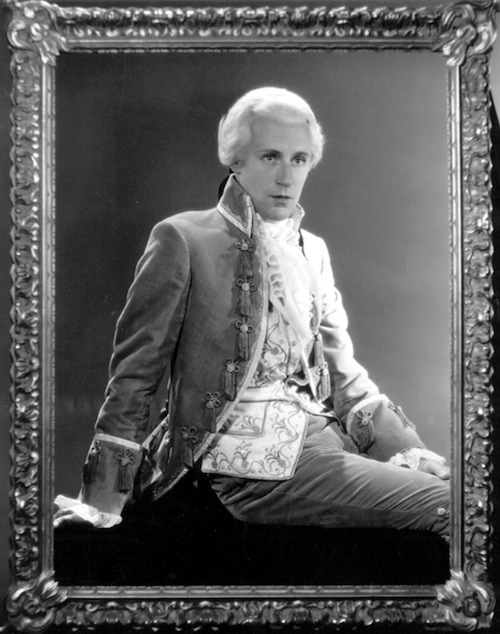

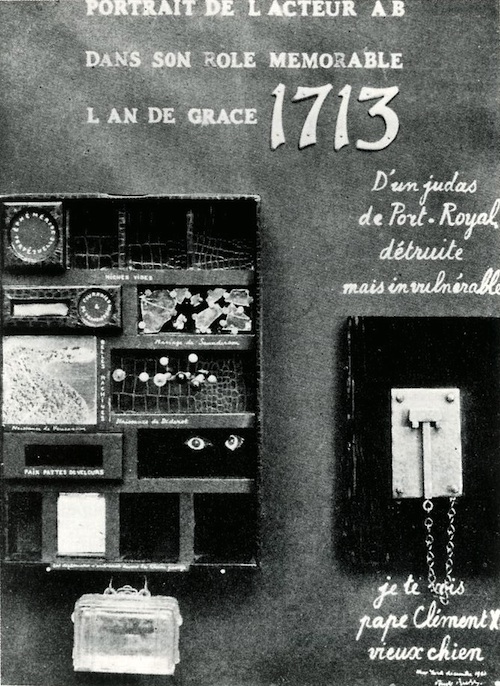

In 1941 Breton made an object poem by the title Portrait of Actor A.B. in his memorable Role, the Year of Our Lord 1713. It bears a premise quite reminiscent of Berkeley Square.

The author’s initial project was to elucidate a particular graphological problem in so far as it affected him. Having noticed that his own signature, when reduced to initials, resembled the number 1713, he was led intuitively to see in this number nothing other than a date in European history and was curious enough to consider what outstanding events occurred during that year (it is entirely possible, in fact, that one at least of these events was of such a nature as to engender in him an unconscious fixation upon a past moment in time , and more specifically a personal identification with that moment).

André Breton: The Object Poem (1942) in Surrealism and Painting

The historical events in 1713 that Breton alludes to are:

- Mistakenly, the marriage of Saunderson.

- The birth of Diderot.

- Mistakenly, the birth of Vaucanson.

- The Treaty of Utrecht.

- The papal bull Unigenitus by Pope Clement XI , which definitely led to the condemnation of Jansenist positions by the catholic church.

The little glass valise at the bottom represents a means for time travelling.

Curiously enough, weird fiction writer H. P. Lovecraft was also very impressed by Berkeley Square. He went to see the film four times and drew inspiration from it for his novella The Shadow out of Time. In one of his letters he wrote:

It is the most weirdly perfect embodiment of my own moods and pseudo-memories that I have ever seen–for all my life I have felt as if I might wake up out of this dream of an idiotic Victorian age and insane jazz age into the sane reality of 1760 or 1770 or 1780 . . . the age of the white steeples and fanlighted doorways of the ancient hill, and of the long-s’d books of the old dark attic trunk-room at 454 Angell Street. God Save the King!

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

Tags: André Breton, Berkeley Square, Cinema, Film, H. P. Lovecraft, Movie, Poème Objet, Portrait de l'acteur A.B. dans son rôle mémorable l'an de grâce 1713, Shadow out of Time, surrealism, Time Travel

Screencap from Peter Ibbetson via Deleuze Cinema Project 1.

What is most specific of all the means of the camera is obviously the power to make concrete the forces of love which, despite everything, remain deficient in books, simply because nothing in them can render the seduction or distress of a glance or certain feelings of priceless giddiness. The radical powerlessness of the plastic arts in this domain goes without saying (one imagines that it has not been given to the painter to show us the radiant image of a kiss). The cinema is alone in extending its empire there, and this alone would be enough for its consecration. What incomparable, ever scintillating traces have films like Ah! le beau voyage (continuity by Albert Lewin – further information via Some Came Running) or Peter Ibbetson left behind in the memory, and how are life’s supreme moments filtered through that beam!”

André Breton: As In A Wood (transl. Paul Hammond) from: The Shadow and Its Shadow

But I can tell here that in 1949 the film Manon, adapted by H. G. Clouzot with the help of Jean Ferry, who was at that time member of the surrealist group, and which established … (Cécile Aubry’s) fame, had moved Breton literally to tears.

Gérard Legrand: A propos de La Femme-enfant in: Obliques N° 14-15 – La Femme Surréaliste

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

Screencap via Cockeyed Caravan

Cinema, insofar as it not only, like poetry, represents the successive stages of life, but also claims to show the passage from one stage to the next, and insofar as it is forced to present extreme situations to move us, had to encounter humor almost from the start. The early comedies of Mack Sennett, certain films of Chaplin’s (The Adventurer, The Pilgrim) and the unfogettable “Fatty” Arbuckle and “Fuzzy” (Al St. John) command the line that should by rights lead to the midnight sun bursts that are Million Dollar Legs and Animal Crackers , and to those excursions to the bottom of the mental grotto – Fingal’s Cave as much as Pozzuoli’s Crater – that are Buñuel’s and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or, by way of Picabia’s Entr’acte.

André Breton, Lightning Rod, preface to the Anthology of Black Humour

This statement appeared beforehand in the magazine Minotaure in a different version. There it concluded with the following sentence which was not included in the Anthology.

It’s for the first time, in 1937, with It’s a Bird, that we are propelled, keeping our eyes wide open to the merely sensory distinction between the real and the fabulous, into the very heart of the black star.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

Tags: Al St. John, André Breton, Anthology of Black Humor, Charley Bowers, Fatty Arbuckle, It's a Bird, Mack Sennett, Million Dollar Legs, Minotaure, Slapstick, surrealism, W. C. Fields

One will soon understand that there was nothing more realist and more poetic at the same time as serials, which not long ago were the joy of free spirits. It is in The Exploits of Elaine, it is in Les Vampires that one will have to search for the great reality of the century. Beyond fashion, beyond taste. Come with me. I will show you how one writes history.

Louis Aragon and André Breton – Le Trésor des Jésuites, 1929

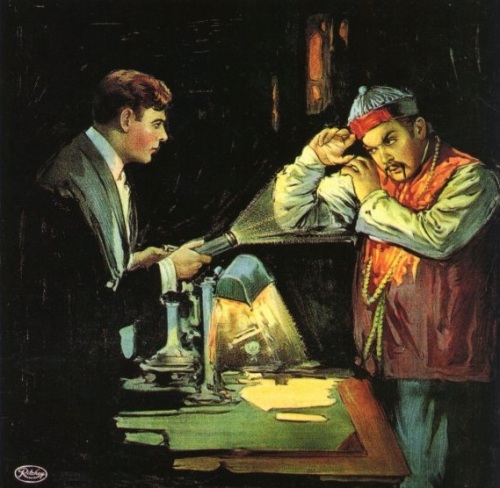

I cannot see, as I hurry along, what would constitute for me, even without my knowing it, a magnetic pole in either space or time. (…) Not even the memory of the eighth and last episode of a film I saw in the neighbourhood, in which a Chinese who had found some way to multiply himself invaded New York by means of several million selfreproductions. He entered President Wilson’s office followed by himself, and by himself, and by himself, and by himself; the President removed his pince-nez. This film, which has affected me far more than any other, was called The Trail of the Octopus.

André Breton – Nadja, 1928

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed

Tags: André Breton, Irma Vep, Les Mystères de New York, Les Vampires, Louis Aragon, Louis Feuillade, Musidora, Nadja, Pearl White, Serial, Trail of the Octopus, Vamp

It’s Too Bad SHE Won’t Live!

A page from the 1982 Marvel adaptation of Blade Runner.

Wouldn’t there be a sort of poetic consistency if the same novel – Henri Rider Haggard’s She – which served as inspiration and respectively source for some of Merian Cooper’s films would have also inspired Blade Runner? I don’t know if this is a fact, but nevertheless, the similarities of the following passage to a particular scene in Blade Runner are quite striking.

Next I retreated to the far side of the rock, and waited till one of the chopping gusts of wind got behind me, and then I ran the length of the huge stone, some three or four and thirty feet, and sprang wildly out into the dizzy air. Oh! the sickening terrors that I felt as I launched myself at that little point of rock, and the horrible sense of despair that shot through my brain as I realised that I had jumped short! but so it was, my feet never touched the point, they went down into space, only my hands and body came in contact with it. I gripped at it with a yell, but one hand slipped, and I swung right round, holding by the other, so that I faced the stone from which I had sprung. Wildly I stretched up with my left hand, and this time managed to grasp a knob of rock, and there I hung in the fierce red light, with thousands of feet of empty air beneath me. My hands were holding to either side of the under part of the spur, so that its point was touching my head. Therefore, even if I could have found the strength, I could not pull myself up. The most that I could do would be to hang for about a minute, and then drop down, down into the bottomless pit. If any man can imagine a more hideous position, let him speak! All I know is that the torture of that half-minute nearly turned my brain.

I heard Leo give a cry, and then suddenly saw him in mid air springing up and out like a chamois. It was a splendid leap that he took under the influence of his terror and despair, clearing the horrible gulf as if it were nothing, and, landing well on to the rocky point, he threw himself upon his face, to prevent his pitching off into the depths. I felt the spur above me shake beneath the shock of his impact, and as it did so I saw the huge rocking-stone, that had been violently depressed by him as he sprang, fly back when relieved of his weight till, for the first time during all these centuries, it got beyond its balance, fell with a most awful crash right into the rocky chamber which had once served the philosopher Noot for a hermitage, and, I have no doubt, for ever sealed the passage that leads to the Place of Life with some hundreds of tons of rock.All this happened in a second, and curiously enough, notwithstanding my terrible position, I noted it involuntarily, as it were. I even remember thinking that no human being would go down that dread path again.

Next instant I felt Leo seize me by the right wrist with both hands. By lying flat on the point of rock he could just reach me.

“You must let go and swing yourself clear,” he said in a calm and collected voice, “and then I will try and pull you up, or we will both go together. Are you ready?”

By way of answer I let go, first with my left hand and then with the right, and, as a consequence, swayed out clear of the overshadowing rock, my weight hanging upon Leo’s arms. It was a dreadful moment. He was a very powerful man, I knew, but would his strength be equal to lifting me up till I could get a hold on the top of the spur, when owing to his position he had so little purchase?

For a few seconds I swung to and fro, while he gathered himself for the effort, and then I heard his sinews cracking above me, and felt myself lifted up as though I were a little child, till I got my left arm round the rock, and my chest was resting on it. The rest was easy; in two or three more seconds I was up, and we were lying panting side by side, trembling like leaves, and with the cold perspiration of terror pouring from our skins.

Henri Rider Haggard: She

Filed under: Uncategorized | Closed